The following contains mention of:

Sexism and misogyny within education and the workplace

Male-led discrimination and violence

Mental health and negative mental health stigma

Sexual harassment, abuse and violence

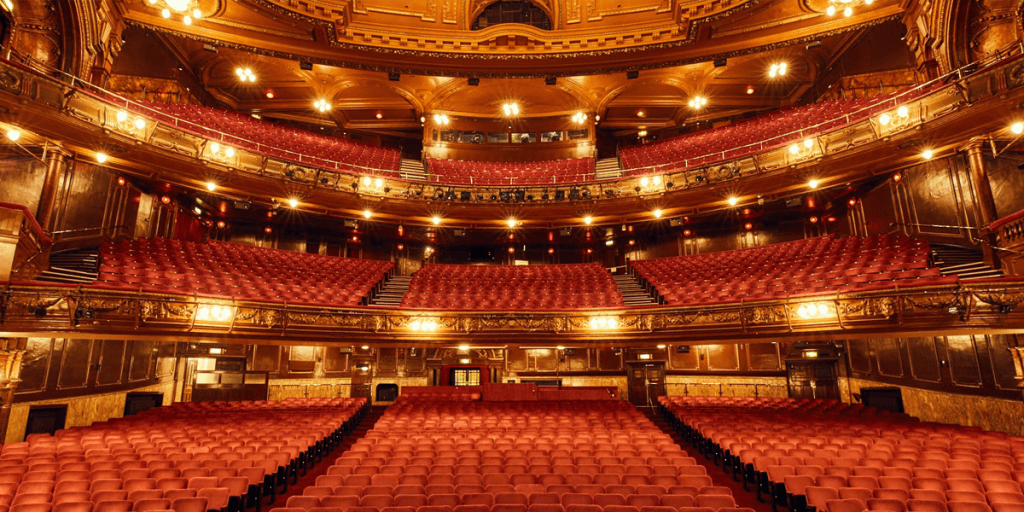

Research for this project has shown that only an estimated 20% of directors in the West End this year were women. Research also uncovered that across 2023, men were around 8x more likely to be credited as a West End playwright than women.

The names on the posters, and by proxy the people able to receive critical acclaim are still largely male creatives. It’s clear that the window of opportunity for women to be either personally platformed or have their work platformed is slim.

This sits at, in the opinion of many, the highest level of our industry, but it must start somewhere. Evidence suggests that this is not only coming from a lack of overall diversity, but a dangerous culture for women in some of the UK’s most prominent conservatoires.

Deadline have recently launched a 5-month investigation titled ‘Drama Schools Uncovered’, analysing the culture of drama schools and their responses when questioned on accusations of toxic learning environments. Deadline have collected multiple accounts contributing to reports of predatory and discriminatory behaviour. Following this work, numerous institutions responded to requests for comment. Institutions referred to their works with external organisations to aid inclusion, as well as a variety of internal developments in staffing and courses structures being taken with the aim of creating a safer and more inclusive space. None of the institutions approached by Deadline agreed to a full interview.

Sky News has recently launched a similar investigation.

Reports from these publications and new channels have shone a light on major incidents within these institutions. These incidents, often rooted in sexist behaviour, are demonstrations of what happens at the culmination of toxic educational cultures, but where does this culture start to grow?

To explore this further, several students and graduates from various south-England based drama schools contributed their experiences with sexism while training. Their names and the names of any referenced institutions have been removed under the promise of anonymity.

One 2021 graduate spoke on how their experience in training has followed them into the industry: ‘Incidents from university, making me feel inadequate for presenting as female, have made me feel like I need to work harder to prove these past people wrong. I feel constantly like I need to prove myself.’.

This individual began their vocational studies in 2019. Similar feelings have been cited by those currently in training.

‘Men would go over my head and bring each other into conversations they weren’t relevant to.’, one student said as they detailed what they believed was sexist treatment while working as a head of department. The same student detailed being treated as if they were undermining creativity when they were undertaking a responsibility to keep people safe. ‘I’d be looked at like I was insane for infringing on a design’.

Further details of this experience included creatives carrying out work that was unvetted and unsafe without the knowledge of the student, and the student having undisclosed contingencies in various areas; they did not feel they were trusted or viewed as intelligent enough to have their work respected.

‘As a woman in technical theatre, I have to fight to be seen as competent while men are just seen as competent.’

Another student detailed a similar air of mistrust:

‘With male students, I wasn’t respected or valued as a source of information, men only seeking guidance from men. I wasn’t involved in important discussions and forced myself into a domineering persona to be heard.’

What sits in drama schools currently is an encouragement to, as this contributor describes it, become ‘the future of the industry’. Post-pandemic, it seemed from the outside as if schools were beginning to acknowledge their faults in regards to varied accusations of harassment when made public.

As we approach 2024, improvements seem to be lacking in many of these institutions. This comes not only from a culture where male students dominate, but also one where male staff are accommodating sexism and undermining.

Discussing their experiences with male staff, one contributor said: ‘My decisions were never viable, and I wasn’t trusted to complete tasks without having a discussion, I was controlled and demoralised – treated like an assistant.’.

There were opposing experiences with female members of staff, stating that they had always been supported as an ‘individual as well as a practitioner.’

‘I have spent 3 years [being told] that the industry is developing to be more accommodating. If I’m treated the same way as I’m treated at [the school], then I want no part of that industry. This isn’t a learning environment. It’s a toxic one, where women are expected to manage working roles as well as misogyny that is being taught to young men by other male professionals.’

The impacts of this are widespread, with multiple students considering leaving their respective institutions. Individuals were consistently told they were wrong, that their work was fine and served the purpose but they ‘could’ve done it differently’. The results of this were ‘irreversible damage’ to mental health and anxiety around working in male-dominated spaces. It was also expressed that perceived inability to do the work at hand was the reason students felt so exhausted; ‘It was only the support of my peers, that had experienced the same thing, that I removed the blame of burnout from myself.’.

Of those asked, no contributors could recall the actions of non-male staff or students contributing to these feelings.

One graduate expanded on their experiences both in drama school and the industry. ‘I’ve always felt like I can f**k up around women. There’s less pressure to get it right first time and be laughed at or looked down on. I’ve seen men do things that are physically dangerous without any consequences, and then I’ve been laughed at for not knowing something. I’m sure there’s a lot of men that feel this way too, but in my experience it’s the men in the space that make people feel insecure. When I’m working now I can see the same thing playing out.’

‘When I think about it now it probably doesn’t help that a lot of the staff I was under in drama school were men, so there wasn’t people there to advocate for me.’

A graduate of a prominent institution spoke on the undercurrent of sexism within their training. This individual has now worked in the sound department for productions both on major UK tours and in the West End.

‘In my entire time at [the school], there was an incredibly obvious lack of diversity of external staff who we worked with on shows. In my three years, working on around 12 shows, I only ever worked with two women.’.

A story was also recounted in which they as a final-year student were told by an external creative to ‘get on with cleaning and tidying the backstage area’, while a male student in their first year was asked to do their practical work. This was work which a student in their first year had not yet been trained to do. The creative in question was later banned from backstage areas but continued to be hired by the school for subsequent productions.

‘In every role I’ve taken, and role at university, I have felt that I was being chosen to do it to fulfil numbers and to tick boxes. Since starting to work in theatre, more often than not I have been the only non-male in the group.’.

Sexism and misogyny being fed to students by staff is a major cause for concern. Involvement in any study at a conservatoire is a large commitment, with heavier working hours than most degrees and a highly pressurised working environment. If staff in these spaces are contributing to the culture of misogyny rather than combatting it, a space is being created in which women are unsafe. Sexism in these spaces is leading students who have committed years of their time to an institution into severe mental distress, and in some instances the urge to leave the schools altogether.

Speaking on their own mental health, one student discussed a production in which they were the recipient of public male aggression and intimidation. The reaction was insufficient, with the female student being removed from the space and the male student continuing with the production. They also felt that this was to do with their status as a member of crew, and that their importance in the space was taken less seriously than that of the aggressor (a performer in the production). During a mental health crisis following this incident, the student said that they were treated as ‘irrational and erratic’ by both staff and students.

‘I felt that as a woman, any emotional response in the world of performing arts was something that should be hidden, otherwise it would be used against you.’

The same student was told during their first term at the school that they had an ‘emotional face’ that they should try to mask, an experience during their training that they believe became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The prioritisation of male students in any space can rapidly spiral into aggressive behaviour and intimidation, something especially prominent in a highly pressurised theatre environment where there are often unspoken power dynamics between different areas of study, as well as staffing hierarchies. These dynamics are only intensified by the vulnerability of training.

Daisy May Cooper, writer and star of This Country and Am I Being Unreasonable? has previously spoken publicly on her experience in training. She discusses the pressure to share personal traumas, and the idea that this felt necessary to be seen and enter the industry as a young person. The pressures on young people in this space are profound, as is the power imbalance between staff and student in relation to employment in these institutions.

One student in these findings spoke of a hierarchy within the courses at their school, and that they felt they were partially unable to report their [male] perpetrator of sexual violence because of this. Although initially not reported, there was knowledge of the incident at the school. ‘After summer I was like, ‘I can’t come back to [the school], I’m scared to be on campus. Their friends and the [course] cohort would all stare at me.’.

The accused student was later permanently excluded after an internal investigation. The contributor detailed ‘massive problems with the code of misconduct’ at the school, as well as with the handling of the investigation. ‘I was always kind of in contact with a woman, they were always in contact with a man who was really high up in [the school].’. There was undermining on numerous occasions, including the student being asked privately to ‘drop everything for one night’ to allow the accused to partake in a school-run public event.

Post-exclusion, the accused has worked professionally under a different name to the one they were reported under.

Although there is a clear thread of institutionalised sexism turning into harassment and violence. These incidents are often unreported, with one contributor noting that it was ‘easier to stay silent’ than to report perpetrators of abuse.

‘I don’t know many people who could be around someone they were already scared of knowing they’d had an email saying you’d reported them. I just couldn’t do it. I knew the report wouldn’t go far either, so there wasn’t much point.’

‘The environment I was in already made it hard for me to accept that I’d been abused. People were so used to men treating women like s**t in every sense that it just felt normal.’

In October 2023, a judge ruled in favour of two former conservatoire students who alleged their college failed to correctly investigate sexual abuse claims. This ruling was 6 years after the initial report. The school followed a common thread: considering all complaints separately, even if there was a collection of complaints against the same student, an element of the investigation considered negligent.

Male platforming in these institutions is escalating from self-indulgence in male dominance to a culture of misogyny, combined with an ignorance towards succeeding violence, something which some organisations are aiming to change.

The organisation Tonic are taking a collaborative approach to drive change, and have worked internationally across numerous theatre companies and conservatoires, with the delivery of workshops and availability of training for individuals. The presence of such organisations within these spaces is itself a signifier of improvement and is an excellent example of restorative action.

Outside of a hyper-specific theatre environment, Emily Test are working with universities to ensure there are provisions in place for institutions to adequately respond to GBV (Gender Based Violence). One conservatoire in Deadline’s work has explicitly mentioned their involvement with this company, a clear step towards change that will strengthen with the support of other institutions.

Although there are given steps towards safer environments, the fall of these institutions is the prioritisation of restorative decisions over pre-emptive action. Institutions, typically when incidents are made public, are often only aiming for resolutions after a major crisis. The notion of addressing institutionalised sexism and misogyny is complex, but the most crucial steps are a wider acknowledgement of the upstanding discriminatory foundations.

The actions being taken by these institutions often involve external organisations and figures. The involvement of unbiased channels is constructive, but only when working on the presumption that action will continue to be taken. At this moment in time, it is difficult to know if this is taking place, especially when the impacts sit not only in conservatoires but industry-wide.

‘Me and a female co-worker used to arrange times to meet during get-outs to see if the other had experienced any comments or inappropriate behaviour from men we were working with – we had to warn each other to look out for certain people to avoid.’, one graduate said about their work beyond training. They later specified that this experience was something that began while they were studying.

‘Being asked these questions ranged from when I started in theatre at 16 to currently, 7 years later.’

Contributions for this research were collected via a variety of recorded and transcribed conversations, as well as anonymous form submission. All contributors undertook involvement with the promise of anonymity. The identity of any contributing individuals, as well as any other contributing research is confidential.

Useful Organisations:

The Survivors Trust – providing a range of specialist services to survivors of sexual abuse, including counselling, support, helplines and advocacy services.

Samaritans – dedicated to reducing feelings of isolation and disconnection that can lead to suicide. Contactable via their website, or via phone at 116 123.

Rights of Women – Providing free and confidential legal advice to women on the law in England and Wales, with a specific focus on Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG)

Leave a comment